“Andy Warhol: Lifetimes”, an exhibit at Aspen Art Museum running through March 27, is similar to recent Warhol shows in Toronto and London — but this one was curated by Monica Majoli.

“The whole concept of the exhibition that the Tate (in London) was putting together was to try to create some clarity about how Warhol’s biography influenced his work,” Majoli said. “That, of course, dealt with elements of his identity as the son of an immigrant, working class — poor, actually — and as a gay man, as a Catholic.”

An accomplished artist herself, often working on themes related to sexuality and intimacy, Majoli brings a refined touch to the project — and ensures that Warhol’s biography doesn’t completely subsume his work.

The main exhibit at Aspen Art Museum starts with unsuccessful erotic works from the 1950s that bombed in New York City, before quickly pivoting to multimedia work from later in his career — including a colorful camouflage acrylic painting from late in his life.

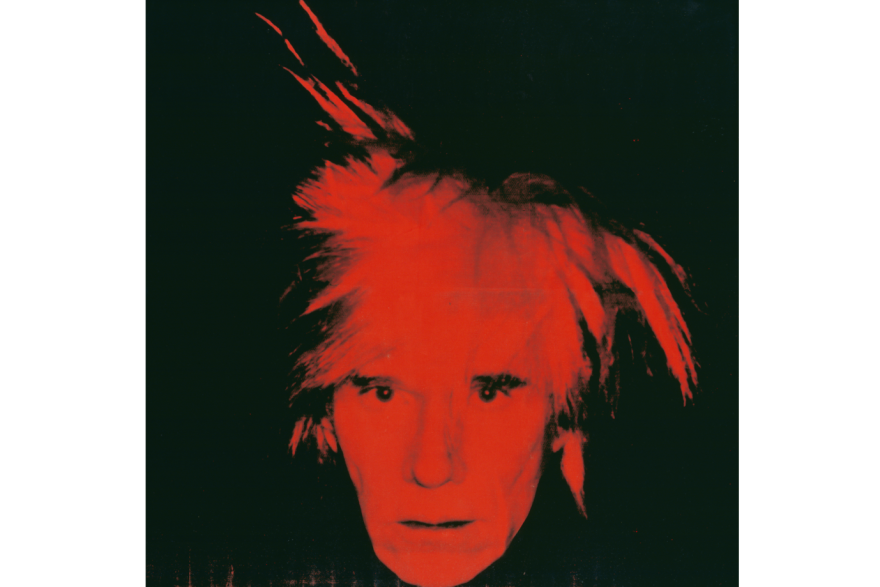

The camo painting captures one of the main themes of the exhibition: Warhol’s intentional masking of his true personality behind a series of flashy personas.

“I was thinking of it within this context as relating both to the idea of being closeted and … Warhol sort of creating this persona, but sort of hiding behind this kind of cloaking that he was doing,” Majoli said.

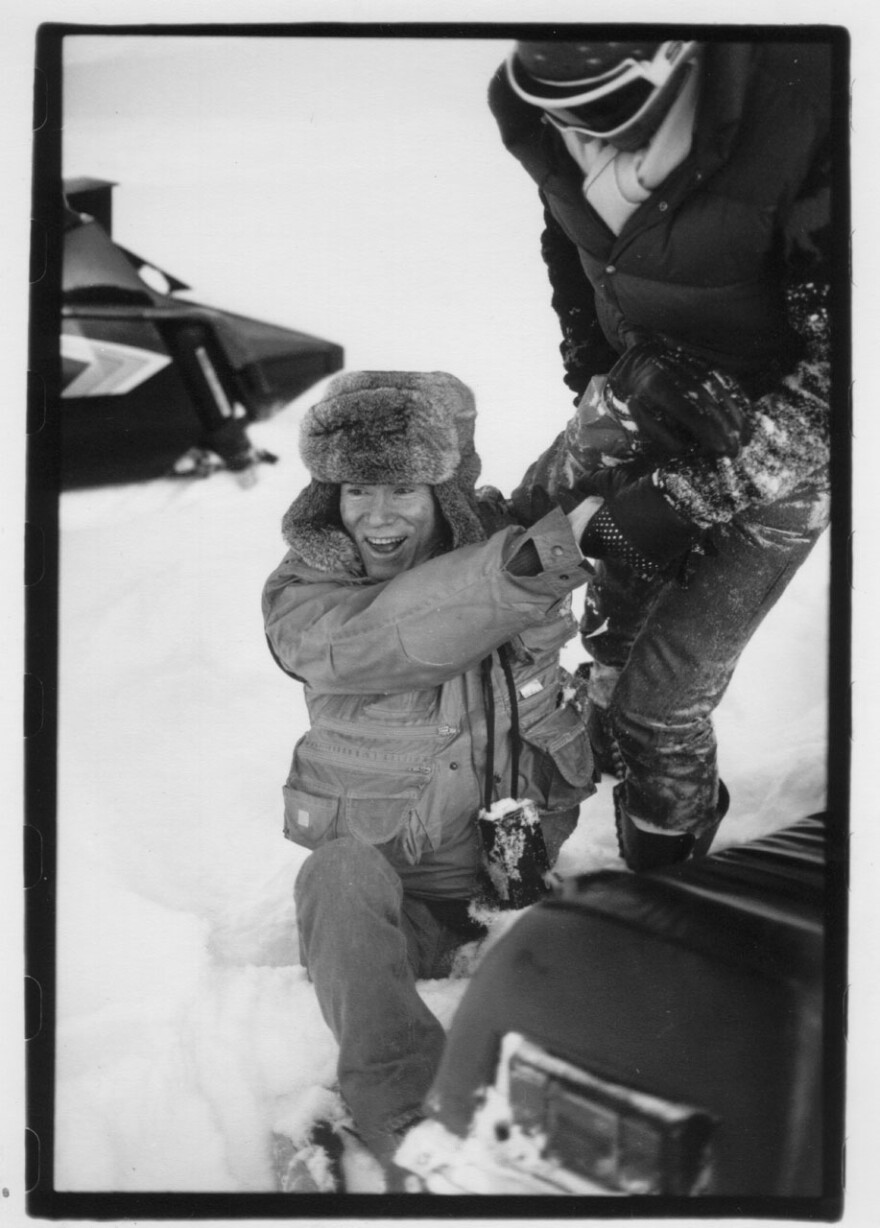

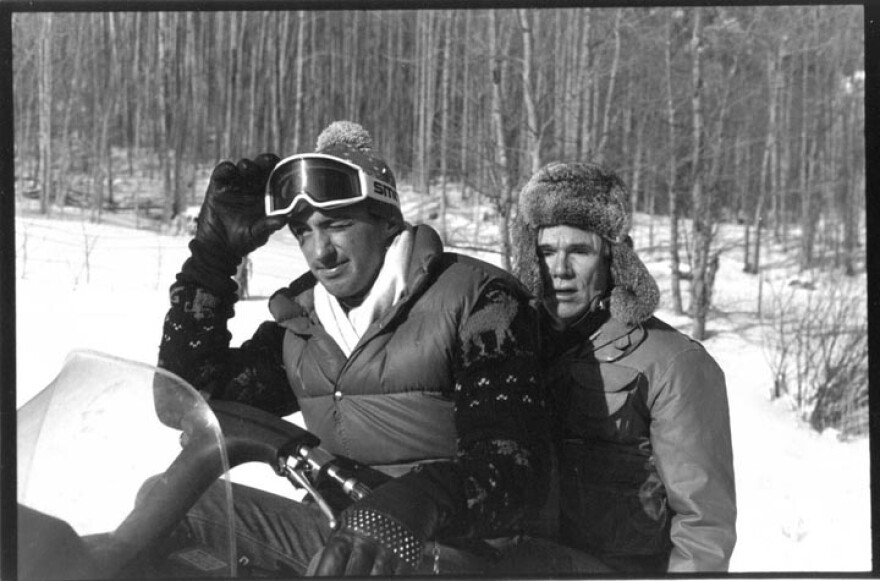

In that exhibit space, we ran into Mark Sink, who had a handful of photographs. The Denver-based photographer knew Warhol and even photographed him in Aspen in the ’80s.

“I pride myself with Andy smiling,” he said, holding up a photo of Warhol in winter gear, partially covered in snow. “He was so happy here.”

As documented by The Aspen Times, Warhol had a 30-year connection to Aspen, with his first recorded visit in December 1956.

Sink’s photos capture a New Year’s visit in the early ‘80s.

“He was very happy here. Look, smiling, smiling, smiling,” he said, thumbing through photographs before arriving at a somber-looking Warhol next to a flipped over snowmobile. “Not smiling — after the snowmobile crash. I dragged my hand in the snow, and it went up in the goggles of his boyfriend John, and off (the snowmobile) went. … I'm the guy that almost killed Andy Warhol.”

The photos — which aren’t part of the main exhibit — capture that emotional side of Warhol that he often kept hidden.

Blake Gopnik is an art critic and author of the 2020 biography “Warhol.”

“He's obviously one of the great figures of the late 20th century — of all time, in fact — in art, and he's unusual, I think, because you have to know about the man to really understand the art, and you have to know about the art to understand the man,” Gopnik said. “And that's not always the case. But with Andy Warhol, I really think that the biography and the art are really closely connected.”

With Warhol, it’s hard to truly know “the man.”

“From a very young age, … he adopted a persona that you could say wasn't really him. It was a persona for the outside world,” Gopnik said. “The thing about Andy Warhol is: He didn't do it once. He didn't establish a persona and stick with it. Every five years, you could say there was a new Andy Warhol. And we've kind of got fixated on the Andy Warhol of the middle of the ’60s – where he's got the dark glasses and he's goofy, and he puts his fingers through his lips and says, ‘Gee, I don't know!’ But that's just one of the personas. And it certainly isn't the real Warhol, who was a super well-educated, incredibly intelligent man.”

On Saturday, Gopnik and Majoli presented “Warhol: Real Love,” a conversation and Q&A at the museum’s rooftop cafe.

It was, as one audience member put it, “Riveting.”

Gopnik is like a guest made for the WHYY program “Fresh Air,” gracefully and succinctly drawing out nuances and contractions in Warhol’s biography. And Majoli — with her sharp, conversational questions — could easily fill in for Terry Gross or Dave Davies.

One throughline of the talk: Warhol’s mother, Julia Warhola.

“She really inspired him when he was a boy, in terms of his artistic proclivities,” Majoli said.

“Yeah, how many immigrant mothers say, ‘Now, son, you must be an artist when you grow up!’ Right? And that's more or less what she did,” Gopnik said.

Warhola, like her son, was an outsider — and marginalization would play a major role in their lives.

“He's not just an immigrant, but he's kind of the wrong kind of immigrant,” Gopnik said. “Everyone knows what an Italian is, what a Jew is, what an Irish person is. How many of you know what a Carpatho-Russian is? He did everything wrong his whole life, he wasn't even the right kind of immigrant. … And I think that touched him his whole life.”

“And his mother, she wasn't even the right kind of Carpatho-Russian. She pretended to be an old country babushka, but she was actually an incredibly complex, sophisticated cultural woman. … She was brilliant and eccentric, and she gave birth to a brilliant, eccentric son.”

And, he was gay.

In Warhol’s public life, his sexuality was something like an open secret — the artist only occasionally nodding at or playfully acknowledging in a roundabout way that he was gay.

But in his work — both public and private — his sexuality plays a more prominent role.

In the first room of the exhibition, opposite from the camouflage paintings, Warhol’s 1964 film, “Sleep,” continuously plays. It shows his lover, poet John Giorno, sleeping.

The movie comes from short reels of film, meticulously compiled and looped to create a truly tender 5½-hour view of Giorno.

Behind it, Majoli placed a room — curtained off — containing nude photos and sketches of men — some in sexual situations — that Warhol would use as references for other work. Most of the material in the room was private throughout his life.

“I thought this room was actually quite important in terms of understanding Warhol as a gay man and his own relationship to his sexuality, and the work that he made in relationship to sexuality and desire, I guess you might say,” Majoli said.

Sink said he thinks Warhol would have been happy to see the private photos made public.

“I think Andy would be very excited, you know, in raising the flag,” he said. “He always asked questions about sex. He was very interested in sex, and he loved the eroticism. And that just wasn't accepted in — especially queer — you know, to be gay. So, as that has come into a more acceptable genre now, I would like to think he would be excited.”

“Andy Warhol: Lifetimes” runs at Aspen Art Museum through March 27.