This story is part of a series following people who get up close to grizzly bears, as the debate rages on about whether they should remain protected by the Endangered Species Act.

It was 7:13 in the morning, and I was driving through fog so dense I could barely see the cars in front of me. There were bison in the meadows, but I didn't stop. I was on my way to meet up with some bear spotters in Yellowstone National Park.

The sky started to clear when I pulled up to a fishing bridge where people were clustered in the parking lot.

" There's a grizzly out here that's gonna walk across this marsh, probably momentarily," said Tanner Haver, an upbeat filmmaker who runs Roaring Mountain Media.

Standing next to Haver is his grandfather, Rick Lee Browning. Browning, a school bus driver from Denver, wears a flannel and scans the marsh with his piercing blue eyes.

Fellow bear watchers had texted them thaty the bear was roaming nearby carrying an elk calf carcass.

"A big bear with a scar across its nose," said Browning, who's been bringing Haver to Yellowstone for 20 years.

" I actually saw my first bear at five," Haver added. "And since then, it was all over."

Yellowstone is already having a record-breaking summer for visitation. About 4 million people come every year, including this family duo. Every summer, Haver and Browning stay in Cooke City, Montana, and make the over an hour drive to areas like the fishing bridge every morning, so Haver can film the bears.

"There's no place like Yellowstone," Haver said. "You have this spectacular stuff happening right off of the highway."

Wearing skinny jeans and Crocs, Haver said we aren't doing much hiking today. We're driving around and waiting for the bears to come to us.

"Alright, I'm giving up on him," Haver said, after waiting about 30 minutes for the scar-faced bear. "Let's go find something better."

We hopped back in the car, and after a couple more stops, we ended up a few miles up the windy road, where dozens of drivers were parked haphazardly staring at something on the ridgeline.

"See her up there?" Haver said, jumping out of the car.

Finally, way in the distance, we saw a 5-year-old grizzly traversing the hillside. We only have a minute with her since she's moving so quickly. Haver doesn't whip out his 40-pound camera setup this time. He already has a lot of shots of this bear since, unlike the scar-faced male, she likes to hang out near the highway.

He's particularly passionate about the bigger bears with battle scars, but he said seeing any kind of grizzly never gets old. It runs in his blood. His family has been around them for decades, in one way or another.

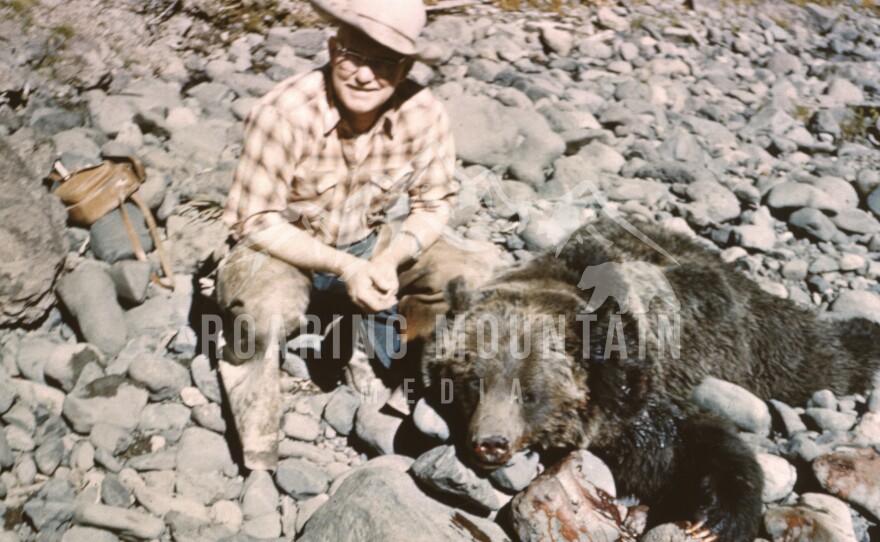

"I've been on three grizzly bear hunts," said Browning. "My uncle ran an outfitters up here. I'd come up and play dude boy for the summer."

Leaning against the tailgate of his truck swiping through old digitized slide photos, Browning said that was right before grizzlies were listed on the endangered species list in 1975, when hunting was still allowed.

"My uncle leased ground from Yellowstone and [the park service] took the rogue bears that had given them trouble the whole year long in the park and dropped them off on the property," he recalled. "And that's the bears that you took the hunters up to hunt."

Now, when bears have conflicts with people, like breaking into cars or getting into trash, they are relocated or euthanized.

"It was a whole different time back then," Browning added.

For years, debate has raged over whether or not grizzlies have recovered enough to be taken off the endangered species list, which would mean states could start grizzly hunting seasons. Environmental groups have fought this, but the leaders of Wyoming, Idaho and Montana have argued that grizzlies have rebounded, with about 1,000 just in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

But in the last days of the Biden administration, the government announced it would keep the bears on the list, so no hunting for now, though the Trump administration could change that.

" I'm not against bear hunts in this ecosystem if it's done properly," said Haver, "and if the management practices aren't completely out of line with science."

"I agree," Browning responded. "But I don't want to see it. I'd rather see 'em with my eyes through the spotting scope, through my camera."

Now a blue sky day, we drove back to the fishing bridge to do just that and hunt for the scar-faced bear, but we'd soon find out we were too late.

"So I take it, he just boogied across this?" Haver asked a group of photographers gathered there.

They told us we had just missed the bear. He had walked right under the bridge.

"Oh no. Owie," Haver exclaimed, stepping back and throwing his hands in the air. "Should have waited. That one hurts me."

But about a week later, Haver got lucky. He happened to come upon the scar-faced grizzly about 30 minutes down the road near some geysers and finally got his chance to get a shot through his lens.

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Nevada Public Radio, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUNR in Nevada, KUNC in Colorado and KANW in New Mexico, with support from affiliate stations across the region. Funding for the Mountain West News Bureau is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Copyright 2025 Wyoming Public Radio