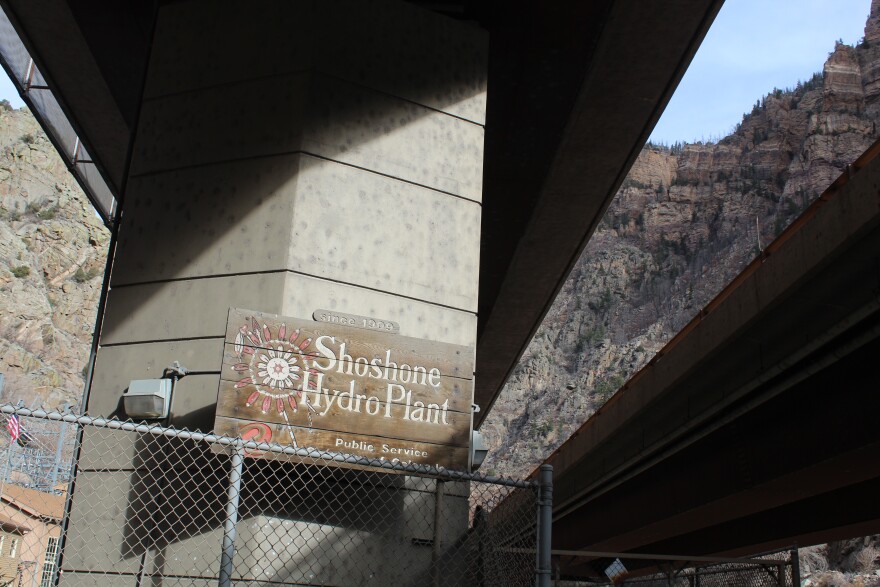

The Colorado Water Conservation Board has approved an agreement with the Western Slope to co-manage one of the oldest water rights on the Colorado River, located at the Shoshone Power Plant in Glenwood Canyon.

The Colorado River District, which represents 15 Western Slope counties, reached an agreement to purchase the water right from Xcel Energy in 2023. There are technically two nonconsumptive water rights that Shoshone uses for hydroelectric generation: the senior one dates back to 1902, and the junior one goes back to 1929. The River District’s pursued the purchase to keep Colorado River water flowing downstream in perpetuity, even if the hydroelectric plant is out of service or shuts down.

One of the terms of the purchase was securing an agreement with the state conservation board through its Instream Flow program. The program is intended to preserve the natural environment of lakes, streams, and rivers in Colorado, protecting the aquatic ecosystems that rely on those flows rather than solely consumptive uses for water. The plan approved on Wednesday, Nov. 19 involves the conservation board and the River District sharing management of the instream flow water right.

Four powerful utilities on the Front Range had some objections to the plan. Denver Water, Northern Water, Aurora Water, and Colorado Springs Utilities worried a co-management agreement would give too much control to the River District, affecting water that could be diverted to fast-growing communities that those utilities serve.

“While the intent is to be collaborative, the result is an overreach,” Abby Ortega with Colorado Springs Utilities said during the six-hour hearing.

Alexandra Davis with Aurora Water agreed. She said that water shortages in the future could mean that water managers might have to make tough decisions about diversions, and that the Front Range didn’t want Western Slope interests putting their thumb on the scale.

“This is exactly why the state needs to keep their authority,” she said. “Because it is a really difficult question, and there might be really difficult questions.”

But representatives from several Western Slope counties across the River District’s area spoke on the importance of the co-management agreement, including Summit, Eagle, and Garfield counties, which the main stem of the Colorado River runs through.

Mesa County Commissioner Bobbie Daniel went one step further.

“If joint management is not adopted, Mesa County will withdraw its support for this acquisition,” she said. “It's not out of anger or politics, but because anything less would fail the people that we serve.”

Daniel said a co-management agreement wasn’t pitting the Front Range against the Western Slope, but rather maintaining a status quo. She also emphasized the importance of the Shoshone’s flows as Colorado and other states in the Colorado River Basin negotiate interstate operating guidelines for the river beyond 2026.

“Joint management protects the existing hydraulic reality, the compact commitments we have never failed to meet, and the downstream flows that keep the entire system stable,” Daniel said. “In a moment when every state is scrutinized for reliability, honoring those flows is essential to maintaining Colorado's credibility, and it also helps us unlock funding potential.”

Taylor Hawes, who represents the Colorado River’s main stem on the Colorado Water Conservation Board, said she was glad there was consensus on the ecological value of the agreement.

“There's no objection to the environmental aspects of this flow, and the purpose of this water right for environmental purposes is really noteworthy,” she said.

For the purchase to move forward, the River District also needs a water court decree approving the change of water rights.

Hawes said water court would be the place to hash out remaining disagreements, and she understood concerns on both sides.

“That is the water court's job and I hope we can all trust that the water court's process will give us a result where we don't have to worry about that — that everyone's concerns will be addressed in that process,” she said.

Hawe also said that she didn’t want to discourage or disincentivize other water users from donating their water rights to the instream flow program.

“There's precedent in other instream flow agreements … with water rights holders who want to have a say,” she said. “If they're donating that water right, it seems like they should have a say.”

“I also think the other thing that was really persuasive to me on that front from a policy perspective was the broad support for this project, including from the people who were objecting to certain aspects of it,” Hawes said. “They all said, ‘We support this project. We support protecting the Colorado River.’ And so, I think that's something that also tells me that this is good for Colorado.”

So far, the River District has raised about $57 million from Western Slope communities to complete the $99 million purchase.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation also committed $40 million for the purchase in 2024, but the Trump administration has frozen those funds. The River District has said that it will now turn its attention to fully securing the money.

Copyright 2025 Rocky Mountain Community Radio. This story was shared via Rocky Mountain Community Radio, a network of public media stations in Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico, including Aspen Public Radio.