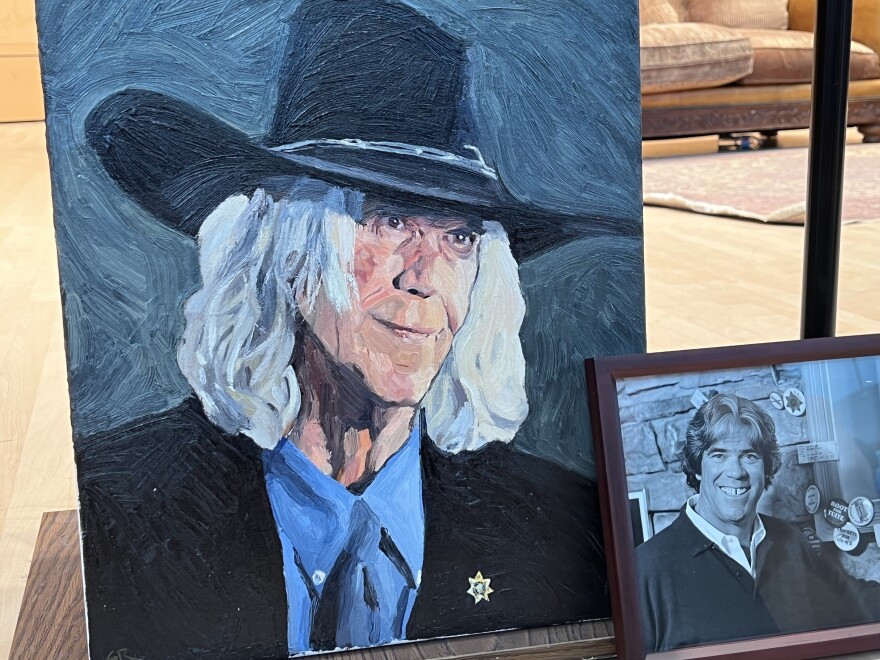

A memorial service was held Saturday for Bob Braudis.

He was first elected sheriff of Pitkin County in 1986 and won reelection five more times, serving 24 years in all.

Braudis died June 3.

He was 77.

Aspen Public Radio broadcast the service live, and the recorded audio of the event is above.

Braudis moved to Aspen in 1969, after graduating from college with a history degree and working as a business analyst and manager at Dun & Bradstreet.

After eight years of enthusiastic ski-bumming in Aspen, he became a sheriff’s road deputy under the philosophical Dick Kienast.

Braudis started as a deputy on March 3, 1977, and worked as a deputy for eight years. He ran for county commissioner in1984 and served in 1985 and 1986.

When Kienast stepped away from the office after three terms, Braudis ran for sheriff in 1986. He would be elected sheriff five more times after that.

In 2000, Pitkin County voters repealed the term limits on the sheriff’s office so Braudis could continue to serve. He did for another 10 years, retiring in January 2011.

Braudis believed that one of the best things he could do as sheriff was hire good local people and ask them to treat people with respect.

He was very much opposed to a macho style of law enforcement, thought drug use was a health issue, not a criminal issue, and said he tried to give everyone who came to him with a real problem the same fair treatment.

Braudis was born in St Margaret’s Hospital in Dorchester in Boston on Nov. 28, 1944.

His father, Robert, was a lieutenant commander in the Navy in World War II. He was at sea when Braudis was born.

Braudis went to Boston College High School in Dorchester, three miles from South Boston, across Dorchester Bay.

“We used to hitchhike to school," Braudis said in an interview in 2001. "If you had a BC High gym bag, you would get picked up in 30 seconds.”

In South Boston, Braudis said, loyalty was prized and snitches were despised.

His father went to work as a sales engineer for Texaco, and the family moved to Buffalo, New York, when Braudis was a sophomore in high school.

“I was uprooted from the 'hood,” he said.

He went to a Jesuit college in Buffalo and graduated from what is now State University Buffalo in 1968.

“They teach you how to study,” Braudis said of the Jesuits. "They teach you how to question. They teach you how to challenge authority.”

He had started out studying medicine, thought about becoming a priest at one point, became a history major and went to law school before running out of money.

Braudis, who married early and had two daughters by 1966, had to leave law school to earn money. He said not completing law school was one of his few regrets.

He got a job as a business analyst at Dun & Bradstreet and went into management.

Braudis spent two years working in the urban corporate world while also protesting in the streets on nights and weekends against the Vietnam War.

“I had friends who were still graduate students, and radicals,” he said. “I got into the hippy thing, the beatnik thing.”

He also had a few friends who returned in body bags.

“I was living in two different worlds,” he said. “And I didn’t like the corporate world at all.”

He visited Aspen twice in the 1960s, in March, and witnessed the magic of fresh snow and blue skies. He had skied and played hockey back East and couldn’t believe the quality of the powder skiing.

In 1969, he moved his family to Aspen, bought a condo and skied — a lot.

“I had 25 three-piece suits when I moved out here,” Braudis said.

He worked as a bartender, a construction worker and a prep cook in Aspen, but essentially, he was a ski bum.

“There was a ton of wasted time,” he said. “A ton of pot. In the spring, someone always had an abandoned couch on their lawn. We’d sit on the couch all day smoking weed watching the moguls melt. We could have gone to medical school in the time we all pissed away, day-dreaming. It was part of the rebellion. We had pretty much ended that evil war, and now we were rebelling against the laws that made smoking pot illegal. If it was legal, we probably wouldn’t have smoked it. It had a cache.”

He said he skied 100 days a year.

“We didn’t carve many turns on the Ridge of Bell," he said. "It was pounding our way down, hot-dog skiing. And then go to work, stay up late, get up and repeat it the next day. It was a religion. Most of my gang here were skiers, ski bums — but intelligent people. It was a golden age here.”

The Jerome Bar became his headquarters.

“I used to look at my check register,” he said. “It would be Jerome Bar, Jerome Bar, Jerome Bar, Jerome Bar, Holy Cross Electric, Jerome Bar, Jerome Bar, Jerome Bar ... buying a lot of whiskey.”

Why did he become a sheriff's deputy?

"In my childhood, some of my heroes were the marshals in the Wild West on TV shows," Braudis said. "When I was a kid, I was always the anti-bully resource. If there was a bully working the crowd, I was the one that would go talk to him and tell him if he persists, he would be the victim of his own bullying. I defended the underdog. I have no tolerance for predators.”

After the shockingly dry ski season of 1976-77, Braudis said he had to get a real job, given he was a single father in his early 30s with two teenage daughters.

When he was hired as a deputy, there was basically zero training, but he realized that he could do 99% of the job just by using common sense and treating people with respect.

Asked what a sheriff does, Braudis was quick to refer to the reign of Aethelred the Unready and go through the history of shires in England and how ”shire-reeve” became the "sheriff."

He noted that sheriffs are still the only law-enforcement officers that are controlled directly by the people through elections, at least in the West.

Braudis prided being accessible 24/7, and said that when he needed to unplug, he left town.

He didn’t like to wear a uniform — and almost never did — because of his disdain for militarism, and he chose to dress as he did in prep school and college, in cotton pants and shirts, and sport coats in the fall.

Braudis credited his success as sheriff to his ability to recruit and retain good people.

“I hire people who, No. 1, are anti-authoritarian, don’t like to be told what to do and generally are creatives — make their own decisions,” Braudis said in 2001. “You hire someone and pretty much trust them to make decisions, big decisions.”