Lea este artículo en español.

The U.S. fertility rate has dipped to its lowest level ever as women have fewer children — or none at all.

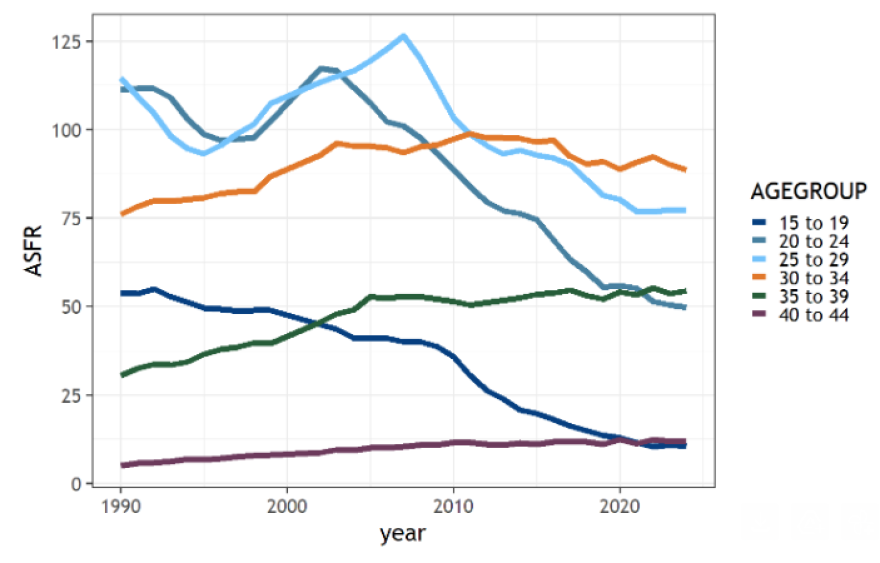

In the Roaring Fork Valley, fertility rates in all three counties peaked in 2007 and have been declining ever since.

Part of that trend is economic as fewer people feel like they can afford kids, including Amelia Dotzenrod.

Despite the economic challenges, she wanted to start a family. It’s also why — like many women — Amelia waited until her mid-30s to start trying.

“I’m someone that probably — at least early on — I've known I've wanted kids,” she said.

But, like many women, she didn’t feel financially secure enough to consider having a baby in her 20s and early 30s.

“The cost of living — it's scary trying to think about life here,” she said. “As prices just go up all around us, it makes you worried even more for making it work here.”

When she turned 32 a couple of years ago, Amelia started thinking more seriously about the decision. Both she and her partner are self-employed, and at the time, they lived in a basement studio apartment — not an ideal situation for starting a family.

But the cost of living in Carbondale and their difficult housing situation were only part of it.

“Some of our biggest concerns about having kids were wanting to do it differently than we've seen our own parents do it,” Amelia said.

She was raised by a single mom who had to work all the time to support Amelia and her sister.

“That sort of thing really — honestly — scares me,” she said.

Despite the economic challenges of raising a family in Carbondale, Amelia saw positives. She thought about how in a small community with a sense of closeness, her kids could just walk over to a friend’s house to play rather than always needing a parent to shuttle them.

“The small-town feel kind of opens up flexibility in that way,” she said.

A little over a year ago, Amelia and her now-husband won Carbondale’s affordable housing lottery. Having stable housing changed their outlook on the feasibility of starting a family.

Shortly after moving into their two-bedroom condo last December, Amelia got a surprise: she was pregnant.

Still, there were aspects of motherhood that Amelia struggled with. It’s more common now for men to take on a greater share of the parenting work than it was a few decades ago, but that didn’t give her much comfort.

“I don't think it will ever feel like they're going to do the same amount,” she said.

Pregnancy only reinforced that dynamic. “I've been doing everything so far,” she said, laughing.

No matter how much progress women have made, Amelia said they still end up shouldering more of the parenting load — especially at first. She had to find her own way to make peace with that dynamic.

“You get to be the one to really, really originally connect with your child in these ways,” she said.

But, 36 weeks into her pregnancy, she still had worries.

The last eight months had been physically and emotionally taxing.

She wondered if it was the right time, or if she was ready, and what the world will look like for her future child.

“A lot of it is more just a lingering kind of background fear of, ‘Oh my gosh, what is it gonna be like for our kid?’”

She thinks about all the things she’s supposed to do as a parent, like starting a college fund, and if it still makes sense. What if college becomes obsolete?

The amount of unknowns could feel overwhelming.

But Amelia also saw glimmers of hope.

“If something's really challenging in the greater American culture, we can come up with ways in our small community to combat that,” she said. “So I think there are challenges in our small community, but also, within a small community, it’s easier to support each other.”

For Amelia, having a child was as much a private decision as it was a choice to believe in her community — and in the possibility of building the kind of support system she wanted.