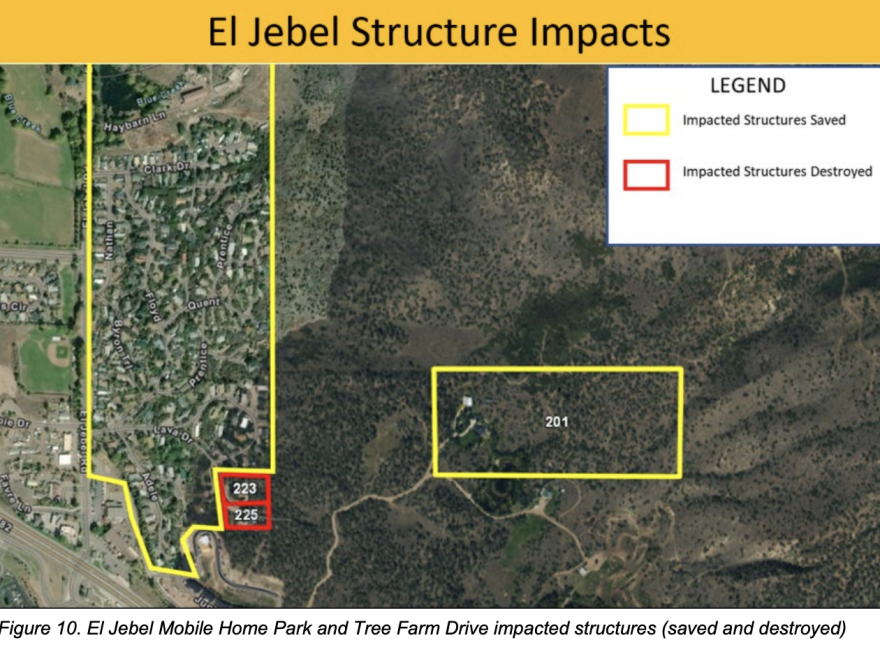

A new report on last year’s Lake Christine fire found that, while firefighters saved homes in the El Jebel mobile home park and Missouri Heights areas, mitigation played a significant role as well; however, making properties more resistant to wildfire requires investments from local communities and homeowners.

Mitigation might include creating a defensible space of at least five feet around structures that have been cleared of flammable materials, such as dry brush or even, in some cases, trees.

Mitigation also refers to “home hardening," or constructing or renovating homes using fire-resistant materials, like replacing a wooden deck with a material such as Trex.

These kinds of projects aren't cheap or easy. Homeowners in the area of the Lake Christine fire, for example, can either pay to dump brush material at the Pitkin County landfill or drive about 60 miles to the landfill in Wolcott.

Another challenge is the amount of properties in the Roaring Fork Valley that belong to part-time residents, who might be coming from parts of the country that don’t face wildfires.

These roadblocks might help explain why REALFire, a wildfire education program in Eagle County that does mitigation assessments, has only seen about 23 properties in Basalt work through all their mitigation recommendations since Lake Christine. REALFire reports doing assessments on over 70 properties.

Eric Lovgren is Eagle County's wildfire mitigation coordinator. He says the time, energy and expense put into mitigation can pay off during a wildfire.

"The return on investment for mitigation work in the preservation of property and human life is massive," he said.

Lovgren is clear that building fire-adaptive communities requires work and resources at all levels.

"So starting at the homeowner level, we want to encourage that initial buy-in, that I play a role in this. I can’t expect the fire department to come and save my house if I’ve done nothing for them to make that possible," he said.

There are some creative ideas when it comes to incentivizing mitigation. After Lake Christine, two streets in the Blue Lake neighborhood close to El Jebel started a competition to see which one would have the most houses mitigate.

"I can't expect the fire department to come and save my house if I've done nothing for them to make that possible."

Encouraging people to mitigate, though, can get complicated. Take, for example, a program that would allow people to bring brush they've cleared from their property to a wood chipper. Lovgren asks, where does that wood chipper come from? Who is in charge of staffing it? Lovgren is a department of one; there aren’t other county staff currently dedicated to mitigation work.

He adds that community partners, such as fire departments, are already stretched thin just fighting fires. Asking them to be experts on both fire suppression and mitigation requires an investment.

Other places in Colorado have seen tax increases that go toward wildfire preparedness. Summit County has a lodging tax to help aid in mitigation costs. However, Eagle County is not currently looking at similar initiatives; county commissioners are interested in growing the REALFire program, but without added resources.

Lovgren says that steps that can be taken include cost-sharing programs from homeowner's associations, new local ordinances regarding mitigation requirements, or grants that help communities undertake more mitigation work.

"Those are some of the places I envision tapping into more than, say, huge tax initiatives and build-up of public resources," he said.

However, communities are eventually going to have to do that too, he said, as the threat of wildfire in the West continues to grow.