The seven states that use the Colorado River remain deadlocked on how to allocate water amid historic and worsening drought conditions. February 14, 2026, marked yet another deadline that negotiators let pass by without submitting a plan to the federal government.

The Upper Basin states of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico are deadlocked with the Lower Basin states of Arizona, California, and Nevada over who will take cuts as climate change worsens the river’s hydrology.

The Lower Basin has already conserved millions of acre feet of water over the past several years, and they’ve committed to even further cuts to water usage. Now, they want the Upper Basin to make its own commitments to conservation.

The three Lower Basin governors released a statement the day before the deadline echoing that line of thought.

“Our stance remains firm and fair: all seven basin states must share in the responsibility of conservation,” the statement reads.

It notes that the majority of the basin’s population, employment, and agriculture are in the Lower Basin, along with most of the Tribal Nations that rely on the Colorado River. They also say that the three states have committed to reducing their Colorado River allocation: Arizona by 27%, California by 10%, and Nevada by nearly 17%.

The Upper Basin says that their water users already take cuts, because they can only use what Mother Nature gives them. In a statement released by the four Upper Basin negotiators, they say water users are preparing for reductions of more than 2 million acre-feet this year, or more than 40% of their allocated water rights. They called these reductions “mandatory, uncompensated, and painful.”

“Meanwhile, our downstream neighbors are seeking to secure water from the UDS (Upper Division States) that simply does not exist,” they wrote.

“We’re being asked to solve a problem we didn’t create with water we don’t have,” wrote Becky Mitchell, Colorado’s lead negotiator. “The Upper Division’s approach is aligned with hydrologic reality and we’re ready to move forward.”

Elizabeth Koebele, an associate professor at the University of Nevada Reno, studies Colorado River governance. She said all of what the states are saying is true, but in the face of a crisis this big, it’s not productive to look at the standards we set for water during a totally different climate.

“I'm not saying we should change the law or break the law or anything like that,” she said. “I'm just saying that we need to find creative ways to build more flexibility into how water is administered.”

There is a possibility that the states will return to the negotiating table.

“The seven states haven’t precluded any more talks,” said Tom Buschatzke, Arizona’s top negotiator in a press release. “We’re all still willing to talk.”

The operating guidelines for the river expired at the end of 2025, and new ones need to be in place by October. That marks the point in time when most of the basin’s precipitation will fall as snow rather than rain, or the beginning of what hydrologists call the water year. Before then, the federal government needs to go through an environmental review and public comment period under the National Environmental Policy Act, which usually takes months.

Koebele said the door is still technically open for the states to weigh in, but they’re running out of time. She said she’d heard June and July mentioned as potential hard deadlines.

“I think even if we had something by then, we'd have a really abbreviated NEPA process,” Koebele said. “The problem is that we're just getting way too close to a deadline to actually go through all of these steps and think about combining alternatives and really getting a lot of robust public comment on them.”

Last month, as part of the NEPA process, the Bureau of Reclamation released a draft environmental impact statement, in which it outlined several paths forward for managing the river, developed in consultation with states, tribal nations, and other stakeholders. This is the normal process for an EIS under NEPA, and usually, the agency responsible for the project identifies their “preferred alternative.” Bucking this convention, Reclamation did not indicate which was its preferred alternative, instead saying that they wanted the states to come to a consensus. The public has until March 2 to comment on the statement.

Koebele says it could potentially get things moving if Reclamation picked its preferred alternative.

“I think that might help move the negotiations forward because it really puts something concrete on the table that the federal government plans to do to manage the river in the absence of a consensus-based alternative,” she said.

All the while, snow drought has plagued the Colorado River Basin since the beginning of the water year.

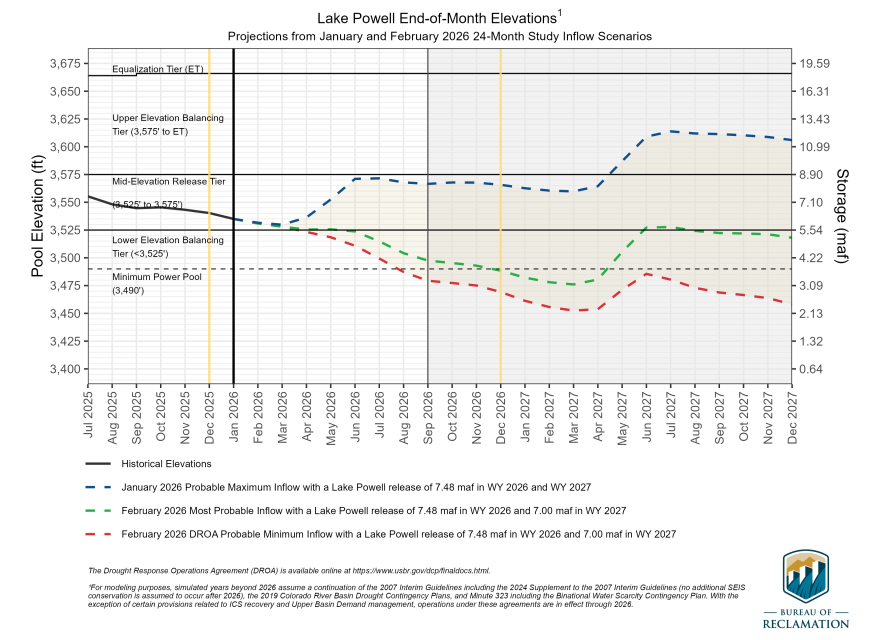

The day before the deadline, Reclamation released its 24-month forecast for Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the two largest reservoirs on the Colorado River. Its predictions were dire, estimating that water from the Upper Basin flowing into Lake Powell would be at just 52% of average for the whole water year, and that that inflow was about 3 million acre-feet of water lower than what was initially predicted in November. That amounts to about 50 feet lower in elevation in Lake Powell than expected.

"The basin's poor hydrologic outlook highlights the necessity for collaboration as the Basin States, in collaboration with Reclamation, work on developing the next set of operating guidelines for the Colorado River system," Acting Commissioner Scott Cameron wrote in the statement. “Available tools will be utilized and coordination with partners will be essential this year to manage the reservoirs and protect infrastructure.”

Koebele said it’s likely that this winter’s drought conditions have put water issues top of mind for the general public.

“As we’re starting to see some of these larger impacts, it sort of raises the salience of water issues for the public, and then that can put increased pressure on the decision makers,” she said.

“To me, if we're thinking about trying to create policies that make our river system resilient for a long period of time, we can't be managing in an ad hoc or crisis-to-crisis way. We can't just be getting together when something bad is happening or we're about to run up against a deadline.”

Copyright 2026 Rocky Mountain Community Radio. This story was shared via Rocky Mountain Community Radio, a network of public media stations in Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico, including Aspen Public Radio.