Across the U.S., women are having fewer children.

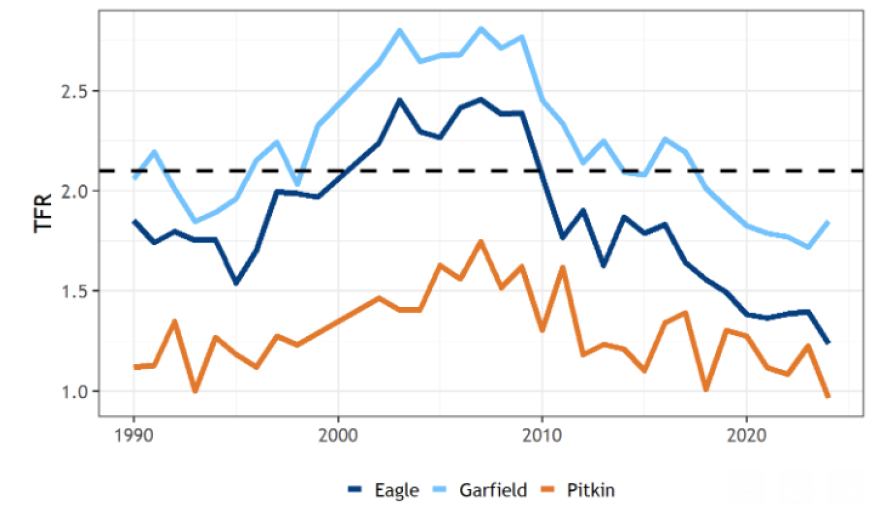

Nationwide, the fertility rate has fallen to its lowest in U.S. history with echoes here in the Roaring Fork Valley, where fertility rates in Pitkin, Eagle and Garfield counties have been falling since 2007.

The trend comes with costs — public schools lose money as enrollment dips, and the workforce contributing to social security shrinks.

But the drop in birth rates also signals deeper, societal shifts, particularly in women’s lives.

The astronomical costs of housing, daycare, and everything else in the Roaring Fork Valley can make the prospect of raising children daunting.

But, for Evelyn Perry, that was only part of it.

“Kids take so much,” Perry said. “They take so much economically. They take so much physically. And to have a child, I've always felt like you need to give everything you have to that life. I would create a life. It is my responsibility for that life to be good, or as good as it can be.”

Evelyn, 34, has lived in Carbondale for six years. She asked her now-husband, Ned, the kids question immediately when they started dating.

“I didn't want to end up in a relationship where one of us felt really certain about it, and the other person felt the opposite, and then we would be unsure of our future.

Ned didn’t want kids. Evelyn did.

“At the time, I wanted kids, and thought I would always have kids,” said Evelyn.

But she wanted to be with Ned, and over time, her feelings shifted. Kids require a lot: time, money, and for women especially, their bodies.

In the winter, Evelyn and Ned work as ski patrollers at Aspen Highlands, often working 12- or 13-hour days. In the summer, they guide river trips on the Grand Canyon and in the Arctic. Sometimes, they’re away for three or four weeks at a time.

For Evelyn, the practical realities of having a baby started to feel overwhelming. To make it work, one of them would have to change their career and find a job with a more normal 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. schedule — and a higher salary.

“I think if both people aren't totally in, then the economics of it — all of it doesn't make sense,” said Evelyn. “And neither of us were totally in.”

Parenting in isolation

There was something else nagging at her: a society that has, in many ways, relegated child-rearing to individual parents.

A conversation with one of her friends, who was a new mother, echoed in her head. For the first few months, she’d been alone with her baby and missed adult conversation.

For Evelyn, it wasn’t just whether or not to have kids. She had to imagine how she would raise them.

“It's a lot easier if you have a society structure where there's a community of people — mothers and aunts and fathers and uncles. Everybody's there with the kids, raising the kids actively.”

Evelyn didn’t see that happening.

“There's a part of me that doesn't want to have a child in an isolated world.”

She also couldn’t ignore the environmental consequences — the carbon footprint associated with having kids. But she knows there’s also a counterargument: the world needs children to fix the mistakes of previous generations.

But the decision to forgo motherhood has rarely felt settled.

“I think it's still nuanced in my head,” she said. “I know it's a ‘no’ — it's a solid ‘no.’ We're going to continue to not have kids. But, I would say emotionally, I still vacillate, because part of me still thinks it would be cool to do that.”

In November, Evelyn and Ned left for a six-month stint in Chamonix, France, for a ski patrol exchange — the kind of adventure that would be a lot harder to pull off with kids.

She’s accepting that her uncertainty might always be there as she holds an appreciation for the life she chose, and, simultaneously, a curiosity about the one she didn’t.